The Case Evolution

Both the electronics and its protective case have undergone a number of significant revisions and iterations; for this post, I’ll be focusing on the case. The case presents the unique challenge in that it’s required to be as waterproof as possible while still allowing measurement of humidity, which takes place on a sensor module inside the case. Those are two mutually exclusive things–humidity measurement requires some kind of opening that water vapor can pass through, waterproofing in its most simple form is blocking all openings.

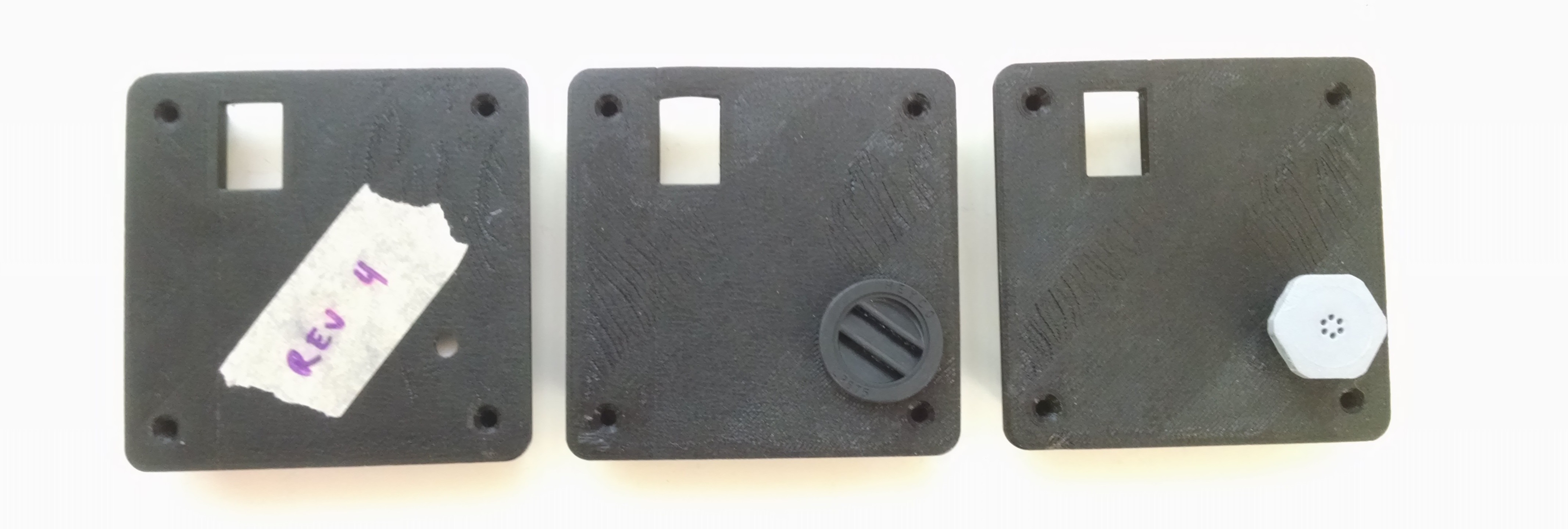

We’ve tried a bunch of different solutions to strike a balance. First, we tried using a couple of breather vents from McMaster Carr–one with louvered panels, another that advertised itself as “liquid-tight.”

We realized that some options were too porous, and some weren’t porous enough. We eventually settled on using sintered metal filters as a humidity port, which are densely packed disks of sintered steel that resist the ingress of liquid water but allow for passage of gases through the screen.

What’s confusing sometimes about these kinds of products is they don’t specify what part of the product is waterproof/water resistant/some other kind of ingress protection.

For example, a switch we bought calls itself IP67–which just stands for Ingress Protection level 67. The first digit, 6, refers to dust resistance (greater is better), the second is for water resistance. There are specific tests you can do to determine the IP rating of your product. But it wasn’t clear to us whether the IP67 rating was for the entire switch, or the switch if you mounted it according the manufacturer’s constructions. What happens if the leads get wet? We’re assuming those aren’t waterproof, right? Can water seep into the housing and mess with the switch action? Deep questions that remain to be answered…

Another aspect of weatherproofing we’ve been looking into and testing out is conformal coating. Conformal coating is a process in which a thin layer of protective chemical (usually some kind of acrylic, polyurethane, epoxy, or silicone) is deposited on a PCB through dipping, spraying, painting or curing. There are advantages to each type of material and coating method, but we’re looking into spray acrylic as it’s easy to apply and relatively easy to rework (remove & redo if something goes wrong or needs to be tested). However, we can’t conformally coat the opening of our humidity sensor, because then it would be unable to log humidity.

The last part of weatherproofing the sensor is the union between the two distinct parts of the case. As the case is now a roughly cylindrical shape, a top and bottom piece will screw together. It’s tricky to get the tolerancing right of the screw threads because the 3D printer we’re using has not had great repeatability, and because we’ve never modeled actually functional threads before. However, we’re confident a combination of 3D printer maintenance tweaks and CAD tolerancing in good threading action.