Testing

We’ve moved into testing the prototype square sensor, which is rather exciting!

There’s a number of things we’re looking for when testing. On the electronics side, it’s battery life, temperature recording fidelity, timing accuracy, and other weird bugs we might not have previously caught. On the mechanical side, we’re making sure the case actually does resist sand and water, the case doesn’t degrade, the battery doesn’t corrode, and the device is easy to operate. Things that cross both fields include making sure the breather vent allows for accurate humidity measurement and that our temperature and humidity readings are actually accurate.

We initially tested the waterproofing of the case in a somewhat dramatic way. We placed the sensor in some water in a vacuum chamber and then turned on the vacuum machine. If the case were at all permeable, the pressure difference between its outside and its inside would equalize–in this case, flooding the inside with water.

The case failed this test. It only lasted to about 680mmHg, or 0.89 atm (roughly 89% of standard air pressure at sea level–and the sensors will truly be at sea level). What we realized, however, is that this kind of testing was overkill. We don’t expect (or plan to support) the sensors being immersed in water for long periods of time or at high pressure. Turtles deliberately lay their nests in places that are intended to be dry, and biologists relocate nests they expect will be submerged to a special area. However, it’s possible the sensors will be dropped in a puddle, which is the kind of use case we are designing for.

Another thing we’re currently testing is the accuracy of temperature and humidity sensor within the case. Our humdity measurements could contain error from a number of sources, but they can be broken up into the case and electrical design.

On the electrical side, there are fewer chances for error–and those that do happen are less within our control. There’s obviously the manufacturer specificied error, but there’s always the possibility a specific sensor has a greater error than the manufacturer guarantees. The data could also contain noise, though that’s more related to how components interact rather than the accuracy of a single reading.

There’s additionally the issue of timing–how do we know that a given temperature reading corresponds to the exact time of day that reading was taken? Our sensor doesn’t have a real-time clock; instead, it uses a system function called millis() that records the number of milliseconds since the circuit received power. Millis() returns an unsigned long, which means that it will reset to 0 after 2^32 milliseconds, or 49.71 days. This isn’t really a big deal even though we’re measuring 65–we’ll just identify the point it rolls over and add it to the previous time in our data processing software.

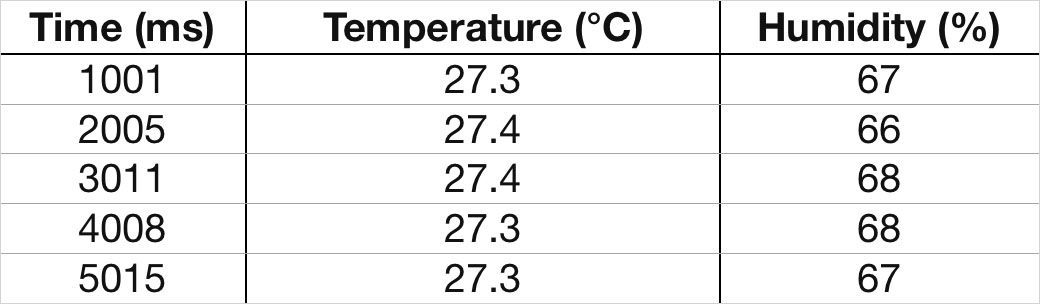

However, due to processing speeds and the error of measuring time to the 1/1000th of a second, we’re not taking temperature measurements exactly every interval (be it 1 sec, 2 min, or 3 hrs) that we set it to. Here’s what our data might look like, taking measurements every seconds to make things easier to see:

Notice how we end up being 15 ms after 5 s. While this isn’t a huge issue here, it could add up over time. But because we’re taking measurements every half hour, the exact second that the temperature is recorded isn’t that important–the temperature shouldn’t change exceptionally rapidly, given that we’re measuring ambient temperature and the sensor will be buried in a nest a few feet underground.

Finally, we’re also making sure that the battery holds up as long as we expect it to. The only way to test this is run the sensor for a long time and see if the sensor still has power when we remove it from the sand.

On the mechanical side, it’s possible that the black housing of the sensor could absorb heat from the sun, causing the sensor to report a higher temperature than it’s supposed to. We don’t expect this to be a huge issue when the sensor is deep within a nest, but it’s something to consider when we’re testing.

We also need to make sure that our breather vent is allowing sufficient air for the humidity to be measured effectively. The way we’re testing this is by comparing the data output for a sensor without a case to one inside a case–if they are significantly different, we know something is up.

We’re testing a few of these factors with our square sensor:

The laptop is taking temperature data from a LabQuest Mini, an educational scientific logging platform. The sensor is buried in the sand close to the temperature probe, which is that black wire sticking out of the sand.

This setup will log data for several weeks, at which point we’ll be able to download the data and compare it to what our sensor spits out.